St James Mansions on the corner of West End Lane and Hemstal Road, were built in 1895.

We look at the history of the building and a few of the people who lived there a hundred years ago.

Before the development of today’s roads, Charles William Clark bought a plot of land and in 1872 he built ‘The Beacon’, a large house and grounds. Clark was an artist and designed the house himself. It was unusual and described as, ‘an exact representation of a ruin on the coast of England showing more than one period of architecture, a monument of human eccentricity, a castle-like dwelling with lofty battlements and turrets.’

Charles died at the house in 1889, and his widow Antonia stayed on until 1894 when she sold it to the developer Edward Jarvis Cave. He and his sons built many of the mansions blocks in West Hampstead, Finchley Road and Maida Vale. The house was demolished, and St James Mansions were built on the site.

|

| St James Mansions today (Dick Weindling, Jan 2021) |

James Hughes Massie

Looking at the 1911 census, in Flat 21 there was Hughes Massie, 35 years old, a literary and dramatic agent, born in Ontario Canada. His wife was Effie Dunreith Massie, 52 years old, born in USA. They had been married for eight years and had no children.

Effie was a writer who had two children by her previous marriage to lawyer James Fraser Gluck. He died in 1897, and she married James Hughes Massie in 1904. The following year they moved to England where Hughes Massie worked for the International Publishing Bureau. In 1906 he and Curtis Brown left to form their own agency which was very successful.

In 1913 Hughes Massie set up his own company and he became the agent of several well-known writers including the notorious Elinor Glyn.

Following her shocking 1907 novel ‘Three Weeks’ which included a scene of love making on a tiger skin rug, an anonymous doggerel was widely circulated:

Would you like to sin

with Elinor Glyn

on a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer

to err with her

on some other fur?

A play based on the best-selling book was banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office.

|

| Portrait of Elinor Glyn, by Philip de Laszlo, 1912 |

In 1915 Elinor Glyn took out a court case against Weston films who made a comedy film called ‘Pimple’s Three Weeks’ which she believed infringed her copyright. It was made by Charles Weston for Piccadilly Films and starred Fred Evans who made over 200 of the comic ‘Pimple’ silent films. She lost her case as the film bore little resemblance to the book.

Hughes Massie’s most famous client was Agatha Christie. In her autobiography she said,

‘He was a large, swarthy man, and he terrified me.’

Hughes Massie is shown in the directories at 21 St James Mansions from 1909 to 1918. But the marriage with Effie had broken down.

On 29 August 1917 Effie petitioned for the restoration of conjugal rights which Hughes Massie ignored. In June 1918 Effie, then living at 22 Belsize Grove, sued for divorce on the grounds of his adultery with Gwyneth Hoos. She was the only daughter of George de Horne Mansergh of 45 The Pryors Hampstead, who in 1912 married Edward Jan Hoos. Hughes Massie was cited as the correspondent in the Hoos divorce in November 1917. In June 1918 Hughes Massie was living at 1 New Court Temple and the following year he married Gwyneth Alice Mansergh Hoos in Islington.

Hughes Massie died on 17 February 1921 at his home 75 Hornsey Lane Highgate, but an agency with his name is still going today.

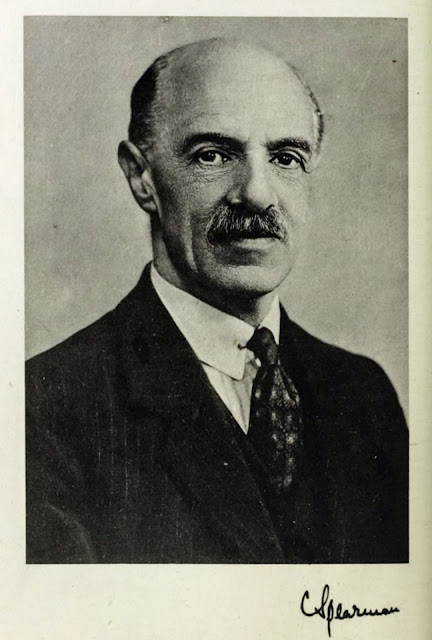

Charles Spearman

Also shown in the 1911 census at Flat 23 was Charles Spearman, aged 47. He lived at St James Mansions from 1909 to at least 1912. He moved to 71 Kensington Gardens Square Bayswater, where he stayed until the mid-1930s. In the 1938 electoral register Spearman was at 67 Portland Court Great Portland Street, which was his address when he died on 17 September 1945.

Charles Edward Spearman was a famous psychologist, born on 10 September 1863 at 39 Upper Seymour Street. His father died when he was two, and his mother remarried Henry Harrington Molyneux-Seel, an official of the College of Arms. The family lived in Leamington Spa Warwickshire, and Charles was educated as a day boy at Leamington College. Aged 19, he joined the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and was based in India where, despite the diversions of polo, poker, and some active campaigning in Burma, he still found time to pursue his boyhood passion for philosophy.

Later his reading extended to psychology, and he was fascinated by the scientific approach that was flourishing in Germany. Shortly after completing a two-year course at the Army Staff College, Camberley, in December 1896 Captain Spearman resigned his commission to study experimental psychology in Prof. Wilhelm Wundt’s laboratory at Leipzig University.

Spearman’s studies in Germany were interrupted by the South African War when the army recalled him to serve as assistant adjutant-general in Guernsey. There he met Frances Henrietta Priaulx whom he married on 4 September 1901 and their four daughters and a son were born between 1902 and 1918.

After his release from military duties, Spearman returned to Germany in December 1902 and began the pioneering work which led to his two-factor theory of human intelligence.

The theory has a common function known as ‘g’, which underlies every intellectual activity. Different activities rely on g to differing degrees and on a specific function, ‘s’, which is unique to the particular activity. How well people performed on any task would be determined by their individual levels of g and s.

The correlational method that he devised to demonstrate the existence of g and to measure it, was the earliest version of the statistical method now known as factor analysis. Not surprisingly, this work, with its promise of an index of general intelligence, attracted considerable critical attention when it was published in 1904.

Spearman pursued a broad range of study over his remaining years in Germany, interesting himself, for example, in spatial perception for which he obtained a PhD in 1906. On his return to England in July 1907 the two-factor theory, and its theoretical implications for psychology, became the focus of his research. This reached its zenith in 1927 with the publication of his book, ‘The Abilities of Man.’

The theory was gradually eclipsed by more complex representations of the structure of human intelligence. None the less, defending the two-factor theory against its detractors kept Spearman and his supporters busy for the best part of three decades.

Spearman had returned home to a part-time appointment as reader and head of the small psychological laboratory at University College London, a post relinquished by his acquaintance William McDougall. Apart from service during the First World War, Spearman remained at University College as professor of psychology until his retirement in 1931. Students came from all over the world, attracted by Spearman’s work on intelligence.

Over forty years Spearman published six books and more than a hundred journal articles. He received many honours including fellowship of the Royal Society (1924), as well as honorary membership of several foreign academies of science. He served as president of the British Psychological Society from 1923 to 1926.

Though ferocious with academic opponents, colleagues found him affable and courteous, though his children thought him rather stern and remote. He was notoriously absentminded about things like briefcases and umbrellas, in contrast to his meticulously ordered academic life. He loved to travel and made many visits to the USA and Europe, as well as touring in India and Egypt. Beyond academic work, Spearman’s passion was tennis which he continued to play into his old age.

|

| Spearman with one of his granddaughters, 1933 |

Spearman’s health and spirits deteriorated in the early 1940s. His son was killed in action in Crete on HMS Orion in May 1941. Spearman had frequent sudden fainting fits which made working almost impossible. He developed pneumonia after a bad fall during one of these blackouts and he was admitted to University College Hospital. Spearman died on 17 September 1945 after throwing himself from a fourth-floor window of the hospital; he had long believed individuals had the right to determine when their own lives should end.

Today, his name is almost exclusively identified with factor analysis, test reliability, and the rank correlation measure which bears his name, but to Spearman the statistical and psychometric work was of secondary importance. Even the two-factor theory was just a part of his search for fundamental laws of psychology.

Emilie Coulson

In February 1912, a tragedy took place in St James Mansions. Charles Coulson who was a manufacturing agent for edged tools, returned home at 1.15 in the afternoon to find the door to the bedroom was locked from the inside. He and his wife Emilie had arranged to go for a meal at a restaurant. He knocked on the door and said, ‘Open the door. Are you ready to go out?’ She replied, ‘I have injured myself, go for a doctor at once.’ He returned with Dr William Slaughter who lived nearby in Flat 9. When Emilie did not open the door, they broke it down. They found her in bed with a revolver by her side and she said, ‘I have shot myself, but I have not been successful. I should have fired up instead of down.’

The doctor found she was wounded in the abdomen. The police and an ambulance were called, and she was taken to St Mary’s Hospital in Praed Street Paddington. Sadly, she did not recover and died three days later.

At

the inquest Charles said the previous year there had been a burglary

in the flat above and Emilie kept a revolver licensed in her name.

He said that Emilie suffered from deep depression and had delusions that people were following her. She had talked of suicide on many occasions. Last year she caught influenza but was not helped by visits to the seaside or to her family in America.

Giving evidence, Inspector Faulkner said Emilie had made several complaints to the police station nearby in West End Lane about the policemen assembling outside who she thought were watching her. The inquest verdict was, ‘Suicide while temporarily insane, following influenza.’

Today, St James Mansions, like many of the other mansion blocks in West Hampstead, is a popular home for people in the area with its large three and five bedroom flats.

Comments

Post a Comment