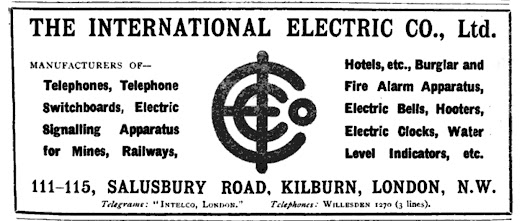

This story takes us to Queen’s Park, Kilburn, Cricklewood and Colindale. It started when I came across an account of the Talkyphone in the Evening Standard of May 1913. I was intrigued as I had never heard the name before. The reporter had visited the International Electric Company (IEC) at 111-115 Salusbury Road in Queens Park. The factory was near the corner with Lonsdale Road but has now been replaced by a modern office block.

The short newspaper article described the process of manufacturing the new domestic telephone. After the raw materials arrived, they passed to the machine shop with a ‘myriad of presses, punches, drills, milling and stamping machines’ which turned out ‘the hundred and one parts of the telephone’. These go to the plating and polishing shops, and the lacquering ovens. Finally, male and female staff assembled the completed instruments.

It is not clear how well the Talkyphone sold as we could not find further references in the online newspapers.

Our research showed the factory was in Salusbury Road from 1905 to 1920. The International Electric Company then moved to Ashley Road in Tottenham and was finally wound up in 1930.

After IEC left Salusbury Road, Siddlers and Sons, an old established printing company, took over the building from about 1922 until 1973.

(We have previously written a story about a fire here in 1935).

The International Electric Company Ltd had been set up by Hermann Oppenheimer, an electrical engineer who arrived in London from Bavaria about 1889. In the 1891 census he was living with his wife and two daughters at 6 Stavordale Road Highbury. He was still at this address when he took British citizenship in 1897. From about 1900 until his death in 1926, he lived locally at 6 Chatsworth Road Brondesbury, near the Kilburn Underground station.

From 1893 IEC had offices at 55 Redcross Street, Barbican, and a factory at Alliance Mills in Stoke Newington. They moved production to Salusbury Road in 1905 and the office transferred there on 1 July 1909. Among their early work, IEC won contracts to make telephone systems for the Council offices of Bournemouth, Portsmouth and Guernsey.

1915 IEC advert

This all looked straightforward until Marianne found Hermann Oppenheimer in the 1921 census. That year the census had added a column which asked for the address of the person’s place of work. He was still living at Chatsworth Road, but his place of work was given as 82 Cricklewood Lane, not Salusbury Road. A search of the Cricklewood directories showed this was the Phoenix Telephone and Electric Works.

Was Oppenheimer so entrepreneurial that he had several telephone companies? This was puzzling until we found two pieces of information. The first was a court case in July 1911 when two men sued Oppenheimer for possession of the International Electric Company which they had funded from Germany. A German court had decided the assets (including the factory) belonged to the two German businessmen and the goodwill belonged to Oppenheimer. The British court agreed, so Oppenheimer lost control of his company.

The second item was a record of Oppenheimer setting up the Phoenix Telephone and Electric Works Ltd on 6 September 1911, as a private company with five other named shareholders.

(We guess the name is probably a reference by Oppenheimer to rising from the ashes).

The factory is shown in directories at 82 Cricklewood Lane from 1912/13 until 1924.

During WWI they produced field telephones for the army. In addition to telephones, they later made tinsel which was a component of the telephone cables.

We found several newspaper articles about the Phoenix Telephone company. For example, in July 1912 Anton Steindorf a 23-years old Austrian appeared in court. He had arrived in England only eight weeks earlier and was working at the Phoenix factory. The foreman Franz Petmeky had fined him for being late and in anger Steindorf had smashed three presses valued at £20 with a large hammer. At the Middlesex Sessions he was ordered to keep the peace for 12 months and pay £7 towards the damages. Coincidently, five months later Petmeky who lived at 218 Cricklewood Lane, was declared bankrupt.

Phoenix Telephones was very successful and needed larger premises, so they moved to part of the Airco site at The Hyde in Colindale Hendon. The Aircraft Manufacturing Company Ltd (known as Airco) had built aeroplanes here from 1912 to 1920. It was established by George Holt Thomas and the chief engineer was Geoffrey de Havilland, after whom the DH planes were named. It grew rapidly during the War and in 1918 called itself the largest aircraft enterprise in the world.

(For more information see Mark Amies book, ‘Flying Up the Edgware Road’).

1937 aerial photo of the factory in Colindale (Historic England)

As part of their WWII effort, Phoenix Telephones set up a second factory in Skelmanthorpe near Huddersfield to produce communication cords for military aircraft.

Phoenix Telephones remained in the family for three generations. When Hermann Oppenheimer died in 1926, Mortimer Epstein who had married his daughter Olga in 1910, took over. After Mortimer died in 1949, his son Edward Nathaniel Epstein became the MD.

The company became a major employer in Colindale and at the peak there were 1,600 staff. There was an active sports and social club and in 1955 the Phoenix Telephones team of four men and two women were awarded a cup for swimming the English Channel.

Phoenix Telephones van 1950sThe Post Office became the single largest customer of telephones and in 1960 a consortium took over Phoenix Telephones. The factory in Colindale was no longer required, and closed in December 1968 when over 1,000 workers, about half of them women, lost their jobs. At the time it was owned jointly by GEC, AEI, Plessey and Standard Telephones.

The factory was later demolished, and the Japanese Yaohan department store opened the Yaohan Plaza shopping centre in August 1993. With different owners, it was later renamed as Oriental City which closed in June 2008 and was finally demolished in 2014. Today the site at 399 Edgware Road is a Morrisons Superstore and blocks of flats.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment