This is a story about the creator of the famous Bentley car, and the Cricklewood factory they built on the corner of Oxgate Lane and the Edgware Road.

Walter Owen Bentley, or as he liked to be known ‘W.O.’, was born on 16 September 1888 at 78 Avenue Road, a large 14-room house in Hampstead. (It was destroyed by a landmine in 1940 and the site has been absorbed into the school complex at the corner of Avenue and Adelaide Roads). Walter was the youngest in the family of six sons and three daughters of Alfred Bentley, a successful businessman and his wife, Emily Waterhouse who was born in Adelaide. Her father was a Yorkshireman, who had gone to Australia and made his fortune in mining and banking before returning to England.

After prep school in Bracknell, Walter, like his five brothers, attended Clifton College, an independent boarding school in Bristol. In 1905, aged sixteen he left to begin an apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway locomotive works at Doncaster. He and his brothers raced motorcycles and he competed in the Isle of Man races in 1909 and 1910. Walter studied engineering at Kings College London for two terms in 1905 and 1906. Leaving Doncaster in 1910, he worked for the National Motor Cab Company at Hammersmith on the maintenance of their fleet of taxis.

In 1912, with his oldest brother Henry Bentley, he acquired the London sales agency of three French cars, the Buchet, La Licorne, and Doriot, Flandrin et Parant (DFP). They began with a showroom in Hanover Street and a rented workshop in an old coach house in the narrow New Street Mews near Baker Street, which in 1929 was re-named as 48 Chagford Street with today’s address of NW1 6EB.

W.O. was a great engineer who made a major contribution to the development of the internal combustion engine by originating the use of aluminium for pistons. Commissioned in 1914 as a Captain and attached to the Royal Naval Air Service, he designed two rotary aero-engines. The Bentley Rotary engine (BR1) was fitted to the Sopwith Camel fighter during WWI. The increased power contributed to the plane’s success in combat, and in 1919 W.O. was awarded the MBE. He also received £8,000 from the Commission of Awards to Inventors, which gave him the capital he needed to fulfil his dream and start his own car company. ‘The policy was simple’, he said; ‘we were going to make a fast car, a good car, the best in its class’.

The new company was formed on 18 January 1919. With Frank Burgess (previously with Humber) and Harry Varley (previously with Vauxhall). By October the first engine was built upstairs in New Street Mews. Bentley designed and built a 3-litre engine and car, aimed at the top of the market, with a high performance for fast, sporting touring. The New Street Mews premises were too small, and Bentley bought a four-acre plot of land in Cricklewood on the northern corner of Oxgate Lane and the Edgware Road.

The Cricklewood Factory (Bentley Motors)

Building work on the Oxgate Lane site began at the end of 1919. In early 1920 a two-gabled brick building was constructed as a engine test centre and the company began the move from New Street.

The first production shops were built. These were steel-framed breezeblock buildings, put up quickly and cheaply. They nevertheless lasted over sixty years, occupied for many years after 1932 by Smiths Industries. A wooden building housed the design and office staff, and at first there were only about 20 staff.

Bentley Motors were less car manufacturers than designers, assemblers and testers. Castings and forgings were bought in, and all machining work was sub-contracted. Chassis frames were made by Mechans of Glasgow and shipped to Cricklewood. Bentley Motors did not build the car bodies themselves. All chassis were despatched to outside firms, notably Vanden Plas of Kingsbury, who built virtually all the bodies on the racing cars and numerous sports four seaters on production cars. Most of the closed cars body work was done by Mulliner Park Ward (MPW) in Hyde Road Willesden. Other companies were also involved.

Inside the factory (Bentley Motors)

The first commercial Bentley was produced in Cricklewood in September 1921 and a total of over 3,000 cars were made there by 1932. They were for the man or woman who wanted the highest in quality and was prepared to pay for it. In 1923 the 3-litre open four-seater, for example, was selling at £1,225 (worth about £75,000 today).

Bentley Motors are shown at Oxgate Lane in the phonebooks from 1922 to 1929. Also shown are their showrooms at Pollen House, Cork Street W1, and the service department in Kingsbury Lane NW10.

At the time, speed and long-distance racing were the best forms of automobile testing and advertising. Bentley cars did well at Brooklands, and they won the Le Mans twenty-four hours’ race in 1924, and again each year between 1927–30, which established the reputation of the company. One of Bentley’s most successful drivers was Captain ‘Babe’ Woolf Barnato, whose father Barney Barnato had left the East End and became a gold and diamond millionaire in South Africa.

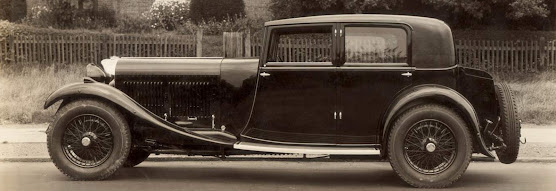

Announced in September 1930, the 8-Litre was W.O.’s final creation at Cricklewood and is widely considered to be his masterpiece. The company proclaimed that with the power of the straight-six engine, the car would be more than capable of 100 mph, regardless of the type of body the owner had chosen. Bentley said, ‘I have always wanted to produce a dead silent 100 mph car, and now I think that we have done it’.

Bentley’s company had financial problems from the beginning and development costs always exceeded the sales income. Financial disaster was temporarily averted when Woolf Barnato put his money in and then replaced Bentley as chairman in 1926. The first year they made a profit was 1929, but it was also the time of the Great Depression and the Wall Street crash which exposed the vulnerability of the luxury car market.

Woolf Barnato decided that he could not continue funding the firm. The company ceased trading in June 1931 and went into voluntary liquidation on 9 September 1931. Napier and Son who made car and aero-engines at Acton, offered £80,000 for the company which included Walter for his design skills. He was very happy and after speaking with the receiver began to design a new Napier-Bentley car. At the High Court meeting on 13 November, which was a legal requirement about the formal transfer, a barrister suddenly stood up and interrupted the hearing. He said he had been instructed by a company called the British Central Equitable Trust to make a higher bid than Napier. The judge said he would not act as an auctioneer and instructed both sides to put their offer in sealed envelopes. When the envelopes were opened, Napier offered £104,775 but BCET won with £125,256. A few days later the identity of the surprise buyer was revealed. To Walter’s horror it was his old rival Rolls-Royce.

The Cricklewood factory was closed in 1932, and production moved to Rolls-Royce in Derby. Some of the employees later said how badly Rolls-Royce treated the old Cricklewood plant.

Walter was bitterly unhappy and played no part as a designer in the new company which was called Bentley Motors (1931). When his contract expired, he moved to Lagonda in 1935. During WWII Walter worked with Lagonda on aircraft and tank components. After the war Lagonda announced a 2-litre car to be sold as a Lagonda-Bentley. But Rolls-Royce went to court to show that its purchase of the Bentley trademark over-rode its contract with Walter, which had banned the use of his name for ten years. The car was then marketed as ‘Lagonda, designed under the supervision of W.O. Bentley’, but the volume of orders could not be met owing to the post-war shortage of steel. In 1947 the firm was sold to David Brown and Bentley’s engine was used in the Aston-Martin DB2 and further developed in its successors.

W.O. in a four and a half litre 1928 car

Bentley married three times. On 1 January 1914 he married Léonie, daughter of Baron St George Ralph Gore. It was a happy marriage but sadly she died in the influenza epidemic of January 1919. His unsuccessful second marriage on 7 April 1920, was to Audrey Morten Chester (Poppy) Hutchinson, the daughter of a barrister. They separated, and Poppy sued for divorce on the grounds of adultery with Mrs Hutton in June 1932, which became absolute on 15 June 1933.

On 31 January 1934 Walter married Margaret Roberts Hutton at Kensington Register Office. Newspapers carried details of Mrs Hutton’s divorce in July the previous year, on the grounds of her frequent adultery with Bentley, and a claim by her husband Charles Hutton for £5,000 in damages. He made the mistake of thinking that the creator of the Bentley was a wealthy man. Fortunately, Walter’s brother was a partner in a good law firm, and the damages were reduced to £1,000 and agreed out of court.

We have traced some of Bentley’s addresses. In the 1911 census he was still with his parents at 78 Avenue Road, and is shown as an engineer in motor cab company. Walter was at 38 Netherhall Gardens in Hampstead in 1917 and 1919. After his marriage in April 1920, he moved to 7 Pelham Crescent Kensington, then to 9 Charles Street by the time of the census a year later. Following his divorce in 1933, he lived at 54 Queen’s Gate South Kensington. Between 1934 to 1936 he was at 4 Addison Road in Kensington with his third wife Margaret. In 1937 and 1939 they were at Melbrook House, Bath Road Staines.

There were no children from any of the marriages. Bentley was living at Shamley Green Guildford when he died at the Nuffield Nursing Home in Woking, on 13 August 1971, leaving £3,121. His death merited a brief mention in some provincial newspapers. But the Times reporter paid a personal tribute, saying that for anyone who owned, or aspired to own one of the 3,040 cars built by the ‘old’ Bentley company under W.O, ‘he was admired and respected, indeed loved is not too strong a word – for to know his cars was to know him’. A worker in his factory described his employer as, ‘a man of modesty, whose lack of pretension, mental honest and reasonableness, endeared him to those in contact with him’.

When Bentley left Cricklewood in 1932, the factory was taken over by Addressograph Multigraph which made addressing machines. In 1936, a newspaper article said their 500 workers were going to get a two-weeks paid summer holiday. The company was there until early 1955 when Smiths Industries who made all types of clocks, took over the site as part of their expansion. Their motor accessory sales and service division were there for many years.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment