We have collected several odd stories from Kilburn which will intrigue and amuse you.

Stealing a baby’s clothes

In July 1867 Jane Cox, who lived at 15 Bridge Street in Kilburn (now demolished), left her two-year old child sitting on the step of nearby Number 7. But when she looked again the child had gone. Some time later a gentleman riding his horse found the baby, naked and crying beside a pond. He took the child to the police who returned it to a grateful Mrs Cox. But what had happened?

Two children, Mary Anne Taylor aged 10, and Mary Rogers aged 9, were responsible for kidnapping the two-year old. In court, it was said both girls had respectable parents and lived at 3 Alpha Place, a section of Canterbury Road in Kilburn. After undressing the baby, the girls went to Charles Tilley, a marine store dealer at 2 Carlton Place, and threw the clothes they had stolen onto his scales. The girls told Tilley that their mothers had sent them to sell the clothes to buy soap, and he gave them a penny for them as rags.

The magistrate decided to send Tilley for trial as a receiver of stolen goods: ‘You knew you were doing wrong, and you lead children into crime’.

We could not find what happened to him. Bizarrely, even though Sergeant Perry said the girls told him they considered throwing the baby into the pond, there was no mention of them being reprimanded. A year later and now named as Charles Tyler, marine store dealer of 2 Carlton Place, was prosecuted for using illegal weights, but he was not fined because of his poverty.

In his book ‘Dickens’ London’ (1987), Peter Ackroyd writes that stealing children and or their clothing was common in mid-Victorian London. In ‘Dombey and Son’, Florence Dombey loses her nurse and is kidnapped by an elderly rag and bone vendor, ‘Good Mrs Brown’. ‘I want that pretty frock, Miss Dombey, and that little bonnet, and a petticoat or two, and anything else you can spare’. After being held for a few hours the woman returned Florence to the streets, dressed in rags.

That Baby!

In 1887 the following story appeared in the newspapers.

The train was just about to start. There were three of us in the carriage – myself and two ladies – when a young man thrust himself in, carrying a baby. He looked very young to be engaged in such a manner. Young men of about 22 years of age (and he looked no older), do not travel about on the underground railway carrying babies: at least, I had never seen any till now. He seemed very awkward with it, and it protested every now and then. The two ladies began talking, and I listened.

‘How nice it is for young men to be so domesticated!’ ‘Yes, indeed. What a little darling it is too – so quiet.’

‘A-a-a! ha a! ha a a!’ remarked the little darling.

‘Shut up,’ said the young gentleman, pinching it.

‘Baahaaahaaa!!’

The ladies assumed a threatening aspect.

‘Sir’, said one of them, ‘babies in convulsions are not usually treated in that manner, and unless you desist at once I shall feel it my duty to call the guard’.

‘I’ll do what I like,’ said the young man, and taking the baby by its long robe, began to swing it round and round, so that its head came in contact with the door frame, after each revolution, the shrieking became terrific.

I got up and pushed him away from the door. Before I could put my head out of the window to summon the guard, however, he laid his hand on my arm, and laid the baby on the seat of the carriage. ‘Look here, old man’, he said. ‘You may call the guard if you like, but recollect that this baby is mine, therefore I’ve a right to do what I like with it. It’s mine – I paid for it.’

‘You what, sir?’ I gasped.

He sat down violently and said, ‘Why what?’

Bang! The train stopped. He got out, leaving on the seat a broken Yankee Rubber Baby.

This was a clever if strange advert for the ‘Yankee Rubber Baby’, a bizarre American import which first appeared in newspapers in 1881, available from an address in Brighton.

After a gap of several years, in 1885 the same advert again appeared, this time with the logo, ‘The Kilburn Rubber Company’. But we haven’t been able to find out the address of the firm.

The unlikely claim was made that ‘even experienced fathers are deceived by these laughter-producing infants and no home can be a really happy one without their cheering presence. ‘The ‘novelty’, which was available as a boy or girl baby, disappeared from sale around 1893.

One a penny, two a penny, hot cross buns!

On Good Friday 30 March 1888, sixteen-year old Cecila Finch, the daughter of a Kilburn bus conductor, ate no fewer than twelve hot cross buns. Unfortunately, they swelled up in her stomach, obstructed her bowel and she died after one of her intestines collapsed. Poor Cecilia was buried a week later in Hampstead Cemetery.

The Cross-Dresser

One night in 1896 PC Gibbs saw a man in the Edgware Road, Kilburn carrying a bridle and halter plus other items. He stopped and asked him what he was doing and was very surprised when a woman’s voice said: ‘Sir, what has that got to do with you? It is my property’. By the light of his lantern he realised he had stopped a woman dressed in man’s clothing. She said, ‘I was going horse riding’. The policeman arrested the woman for stealing the equipment, valued at 15 shillings, from a stable at the Brondesbury Stud Farm. When 39-year old launderess Mary Anne Hester of 3 Springfield Terrace, appeared in court, she said in an educated voice that she had told the policeman: ‘Take them home and tell the servants that I shall not go riding this morning. I left my blue shirt in the stable’. This was greeted by much laughter, but the magistrate was not amused and sentenced Mary Anne to a month’s hard labour.

Body Parts

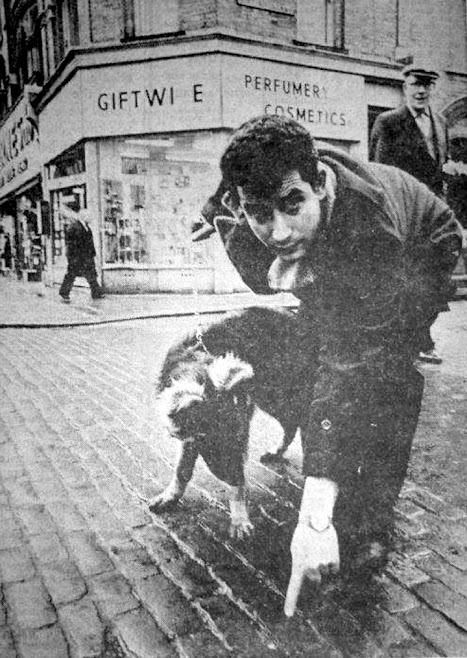

In February 1967, Nicos Sotiriou, a waiter from the nearby Apollo Restaurant at 250 Kilburn High Road, was walking his Alsatian puppy late one night when he came across the gruesome remains of a woman’s severed arm, at the corner of Burton Road and Kilburn High Road. Gerry McCann who lived in Buckley Road called the police.

Nicos Sotiriou and his puppy Jenny (From The Kilburn Times)

Then another forearm and 50 to 60 pieces of flesh were found in Grangeway near the entrance to Grange Park. There was red nail polish on the fingers. The police sealed off the area and a large forensic search was carried out by 30 officers. A police spokesperson said ‘This is one of the most horrific crimes I have ever seen’.

A murder investigation headed by Chief Superintendent Fred Gerrard and DCI Eric Miller was begun to find the sadistic killer. There was a massive search to identify the victim and it was front page news in the Daily Mirror of 1 February.

Later, Dr Roland Teare, a Home Office pathologist, confirmed that while the flesh parts were probably animal, the two forearms were certainly human. After several weeks, the police concluded it must have been a macabre hoax using body parts stolen from a medical school or hospital.

A previous version of this blog was published in West Hampstead Life in 2013

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment